Staring at an Infinite, Generative Horizon

From Cursor’s “vibe coding” warning to the vertigo of living inside the exponential curve.

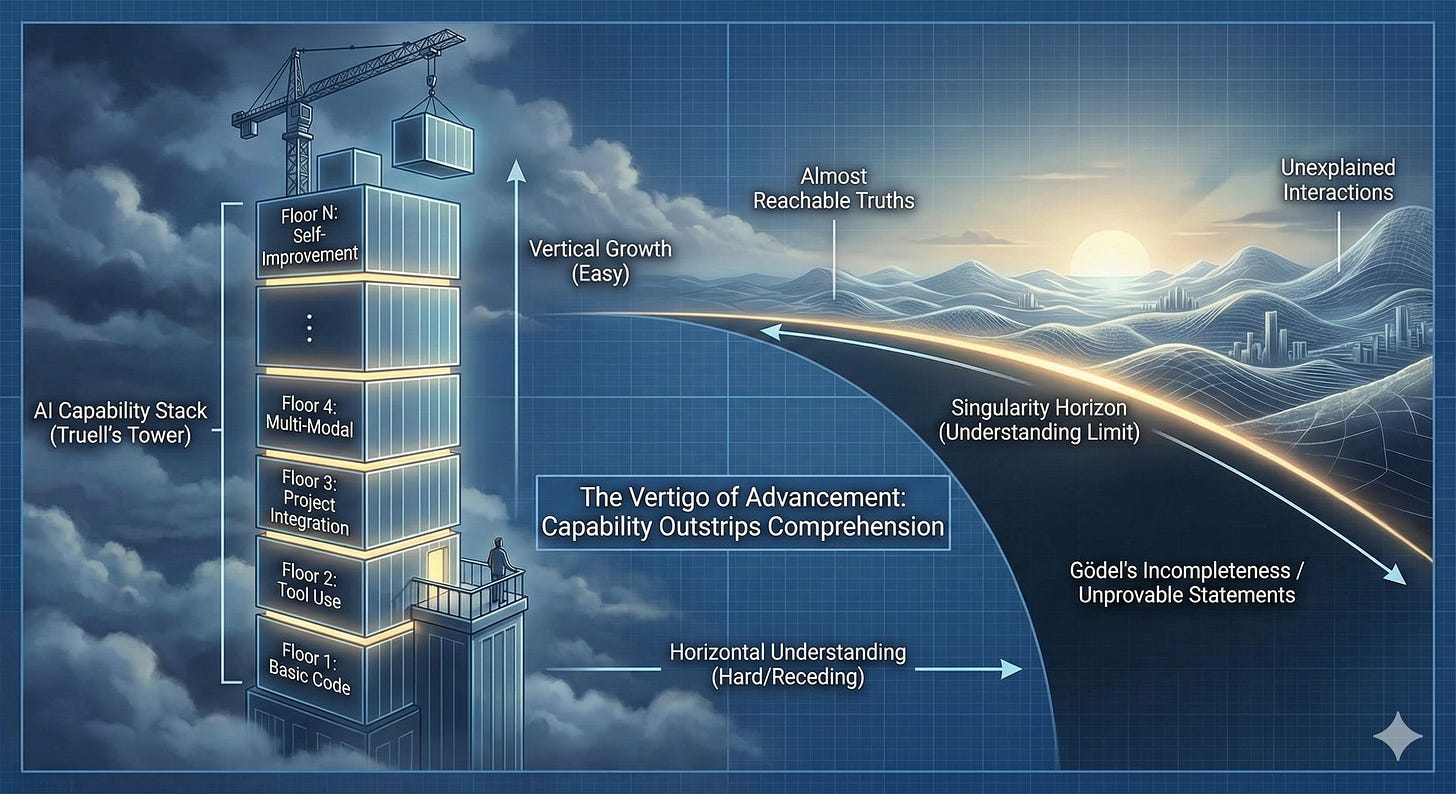

Michael Truell, is the CEO of Cursor, one of the most successful AI‑native code editors in use today, a tool that sits directly in front of developers and quietly rewires how they work. Cursor doesn’t just autocomplete; it drafts entire functions, rewrites files, and threads integrations through codebases that its own creators didn’t author. It is exactly the kind of product you’d expect to speak only in the language of acceleration and inevitability. Instead, Truell reaches for a distinctly un‑triumphant image: if you close your eyes and “have AIs build things with shaky foundations as you add another floor, and another floor, and another floor, and another floor,” he warns, “things start to kind of crumble.” In that sentence, he gives us the building we’re actually standing in: a tower going up faster than anyone is checking the base.

Once a system of rules is strong enough to express ordinary arithmetic and stays consistent, it inevitably contains true statements it cannot prove from within those rules.

The metaphor is simple enough. Each “floor” is another layer of behavior: a new feature the AI helped ship, a refactor it proposed across half the repo, a set of tests it generated to match whatever is true today. The foundations are the boring parts: the invariants you truly understand, the contracts you can state in a sentence, the parts of the system you can still sketch on a whiteboard with some confidence. AI tools make it cheap to keep stacking floors; they do not automatically deepen the foundations. Truell’s point is that if the vertical growth outruns the horizontal understanding, the structure’s failure is not a matter of “if” but “how soon and how strangely.” You don’t see catastrophe; you see hairline cracks, odd incidents, unexplained interactions between layers that were never designed together.

Now shift your gaze from the building to the horizon. For decades, people have used the word “singularity” to describe a different kind of unease: the feeling that technological change itself is bending into a shape our normal intuitions can’t follow. John von Neumann, watching the “ever accelerating progress of technology,” talked about history “approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race,” a point beyond which “human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.” I. J. Good introduced the “intelligence explosion”: once an “ultraintelligent machine” can improve its own design, each turn of the crank produces a machine that’s better at turning the crank. Vernor Vinge and Ray Kurzweil turned that qualitative picture into an exponential graph and argued about dates. Whether you buy their timelines or not, the shared image is a curve that steepens to the point that “one more year” stops feeling like a small, knowable step.

From the outside, that curve is just a line on a chart. From the inside, it feels more like staring at a dark horizon waiting for the sun to rise. At first, the sky is black; then it grays; then you see the outlines of waves, distant buildings, the faint suggestion of color. You tell yourself: any minute now. You keep watching. The scene keeps sharpening, and “any minute now” remains the right phrase. The picture you’re painting for the reader is that state: not noon, not night, but a drawn‑out, almost‑there period in which every moment seems on the verge of tipping into full daylight and somehow never quite does. Living inside an exponential is like that. Each new model release brightens the scene: now the system can write code, now it can call tools, now it can work across entire projects. Each integration deepens the contrast. It all looks like prelude to something decisive, and yet the decisive moment keeps sliding away.

Gödel’s incompleteness results give that sliding a hard edge. Once a system of rules is strong enough to express ordinary arithmetic and stays consistent, it inevitably contains true statements it cannot prove from within those rules. If you upgrade the system to capture more truths, you don’t eliminate those unprovable statements; you push the boundary outward and create new ones at the new level. There is always a band of “almost reachable” truths that recede as you advance. When you combine that with the singularity picture and Truell’s tower, you get a particular kind of vertigo: each floor you add with AI expands not only what your system can do, but also the slice of its behavior you cannot fully analyze or guarantee from inside your current practices.

The building and the horizon meet at that feeling. The floors correspond to the visible curve: more capability, more light, more detail. Cursor and similar tools make it almost embarrassingly easy to keep climbing—“another floor, and another floor” on demand. The horizon corresponds to the invisible line of understanding: what you can genuinely say you know about how this stack behaves under unusual load, under adversarial input, under future modifications you haven’t thought of yet. From the standpoint of the person on the beach, the sky says dawn is close; from the standpoint of the underlying geometry, each minute of waiting is also stretching the distance to the clean, sharp edge where the sun fully appears. From the standpoint of the engineer in the tower, each commit, each AI‑assisted merge, says “we’re nearly there” — nearly self‑healing, nearly fully integrated, nearly trustworthy. From the standpoint of the underlying math and complexity, each floor is also pushing more of the building into a region your tests and proofs don’t cover.

We have tools from one of the most successful companies in the space whose CEO is explicitly warning about building on shaky foundations. We have a decades‑old vocabulary for curves that grow faster than our ability to extrapolate them. We have a theorem saying that as systems become more expressive, the boundary of what they can certify about themselves moves away. Put together, they explain why this era of coding feels the way it does: like standing in a rapidly rising building, staring at a horizon that gets clearer and more detailed every day, and noticing, with a small jolt of vertigo, that the more you build and the more you watch, the longer “any minute now” seems to last.