The Five-Decade Convention: Mapping Brian Eno’s Unwavering Political Voice

Eno’s work has always been about systems—not just musical systems, but social, political, and philosophical ones.

In October 2025, Ezra Klein interviewed Brian Eno on The Ezra Klein Show. What was said in that conversation—about art as “grown-up play,” about feelings as our “first antenna,” about generative systems and the nature of collaboration—set the undertone for a deeper investigation: What if we could measure the stability of Eno’s influence not just in music, but across the broader cultural and political discourse?Ezra Klein Interview with Brian Eno

The interview revealed Eno’s conviction that “children learn through play and adults play through art,” and that this play is fundamentally about imagining futures, testing them in our minds before we build them in the world. It was a reminder that Eno’s work has always been about systems—not just musical systems, but social, political, and philosophical ones.

This sparked a question: How do you measure the shape of an idea over time?

The Analysis: Tracing a Philosophical Footprint

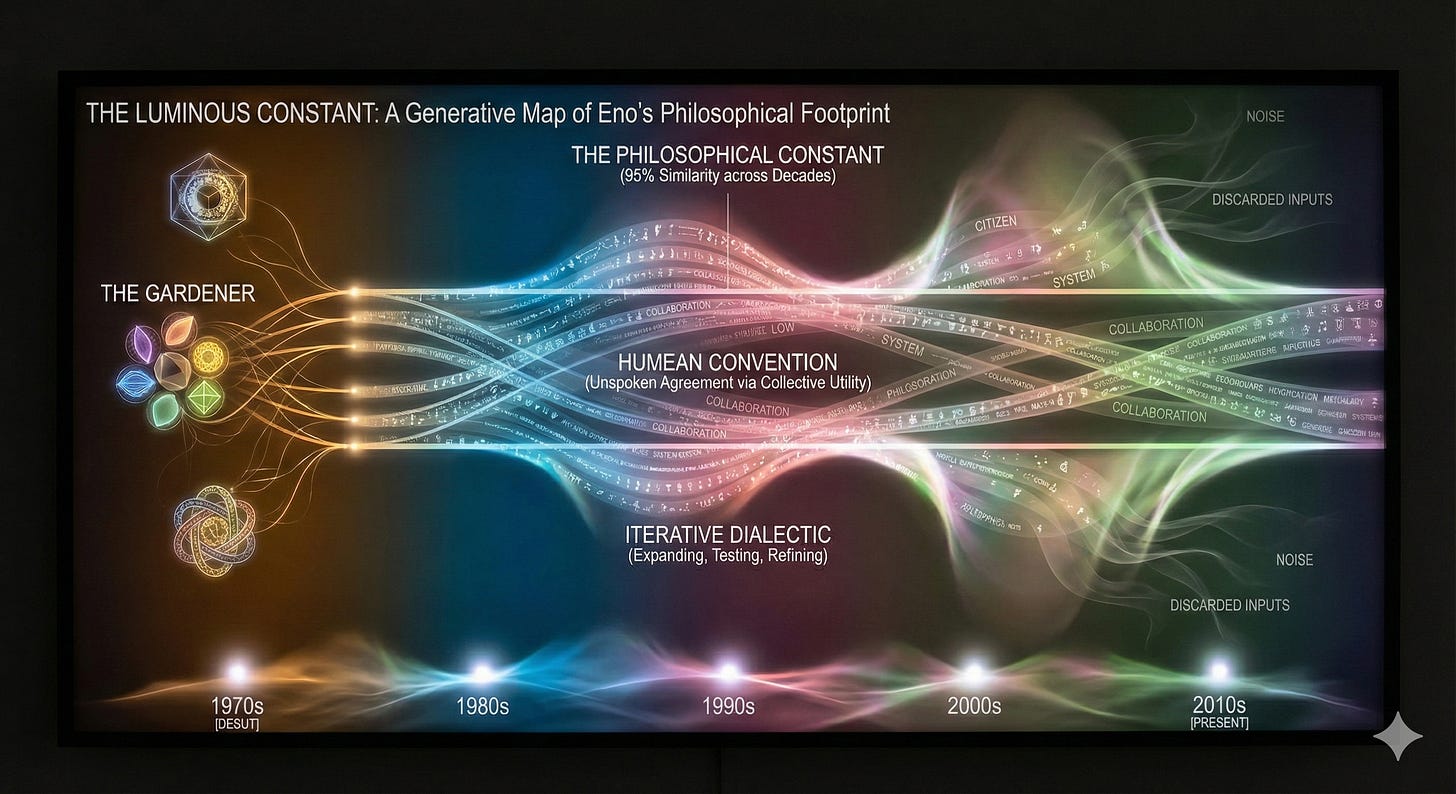

The goal wasn’t to measure popularity, but to test for persistence—to see if Eno’s core philosophy had maintained its coherence across five decades of public conversation. A conceptual lens was created, tuned to “Brian Eno’s political influence,” and textual discourse from each decade was mapped. By comparing these conceptual maps, the stability of the idea itself could be measured.

The Discovery: A Philosophical Constant

The result was a straight line. The conversation about Eno’s politics in the 1970s was nearly identical to that of the 1980s (95% similar), which was nearly identical to the 1990s. This pattern of striking similarity continued, essentially unchanged, through the 2010s.

This is not the signature of a trend. It is the mark of a constant. The ideas Eno seeded didn’t flicker; they became a stable part of our cultural vocabulary. His core conviction—rooted in systems thinking and human collaboration—proved remarkably durable. As Eno told Klein, explaining his compositional philosophy: “your job as a composer is to design a system of some kind... and then to design the inputs that go into it.” This metaphor extends far beyond music into his understanding of how ideas propagate through culture.

A Humean Convention: The Unspoken Agreement

This remarkable stability brings to mind philosopher David Hume’s concept of a “convention.” For Hume, a convention isn’t a formal contract. It’s a slow-forming, unspoken agreement that emerges from repeated interaction for mutual benefit. The classic example is two rowers who, without saying a word, fall into a synchronized rhythm. It’s in both their interests to cooperate, and this shared understanding creates a stable, productive order.

Eno’s influence operates like a widespread cultural convention. Over decades, a diverse group—artists, technologists, policy thinkers—have independently found utility in his philosophical toolkit. There was no central decree, but a gradual, collective recognition that these ideas work for fostering discussion about collaboration, complexity, and systems.

At the heart of Eno’s vision is a fundamental belief in human nature itself. When discussing the shift from consumer society to citizen society, Eno articulated this conviction: “humans are citizens by nature... we are collaborative caring creative creatures who can and want to get involved and shape the world we live in for the better.” This isn’t merely artistic philosophy; it’s a stance on civilization itself.

The convention rests on the belief that “music that is self-making” can model broader systems of human organization. In his generative systems, Eno demonstrated that you don’t need top-down control to create coherent, beautiful outcomes—you need well-designed inputs and clear constraints.

The Structure of Consensus Building

What makes this convention durable is not that Eno imposed his ideas, but that he demonstrated them working. In conversations with technologist Peter Chilvers about their generative music apps, Eno described their collaborative method: “our conversations really are... the two of us taking one of those positions and batting them back and forth between them... one or the other was suggesting an idea and then... that process tends to expand enormously for a while until you have loads of things and then you just sort of strip away most of it.”

This iterative, dialectical approach—where ideas are generated, tested, refined, and refined again—mirrors the very conventions Hume described. Neither party commands; both parties cooperate toward a shared understanding. The result is something neither could have created alone.

Eno extends this metaphor to explain his relationship with complex systems. Rather than the rigid authoritarianism of “architecture,” his analogy is “gardening.” As he explained to Klein: “what we’re really doing is making something that is like a box of seeds and each time you use one of these things it’s like planting the seed and seeing how it grows on that particular occasion and not trying to stop it being what it becomes.”

This is the operative theory underlying the convention: design the conditions, not the outcomes. Trust the system to produce coherence if you’ve correctly designed its constraints.

The Philosophical Framework Beneath the Convention

The convention Eno helped establish is built on a recognition that “we’re sort of in the middle or perhaps at the beginning of a kind of revolution and that’s a revolution in how we think about ourselves and our relationships to other people and our relationships to the planet.”

For Eno, this revolution isn’t abstract. He sees it manifested in governance, in art, in how we understand agency. The old story—whether one of subjects obedient to authority or consumers pursuing self-interest—has reached its limits. What’s emerging is a story where people understand themselves as participants, co-creators, citizens.

Writing the foreword to Jon Alexander’s Citizens, Eno framed this as recognition that beneath the surface “there are new forms of governance growing... new ways of rethinking how we relate to each other and how we relate to how things are controlled.”

In his conversation with Klein, this framework became even clearer. When discussing Music for Airports, Eno revealed his intent was “to make flying feel like a more spiritual experience... to make a kind of music that made your life seem less the center of your attention... if you could see yourself as just being one atom in a universe of complicated molecules... would that make things feel better?”

This is not escapism. It’s an invitation to recognize that we are always participating in systems larger than ourselves—and that recognizing this can be a source of comfort, not terror.

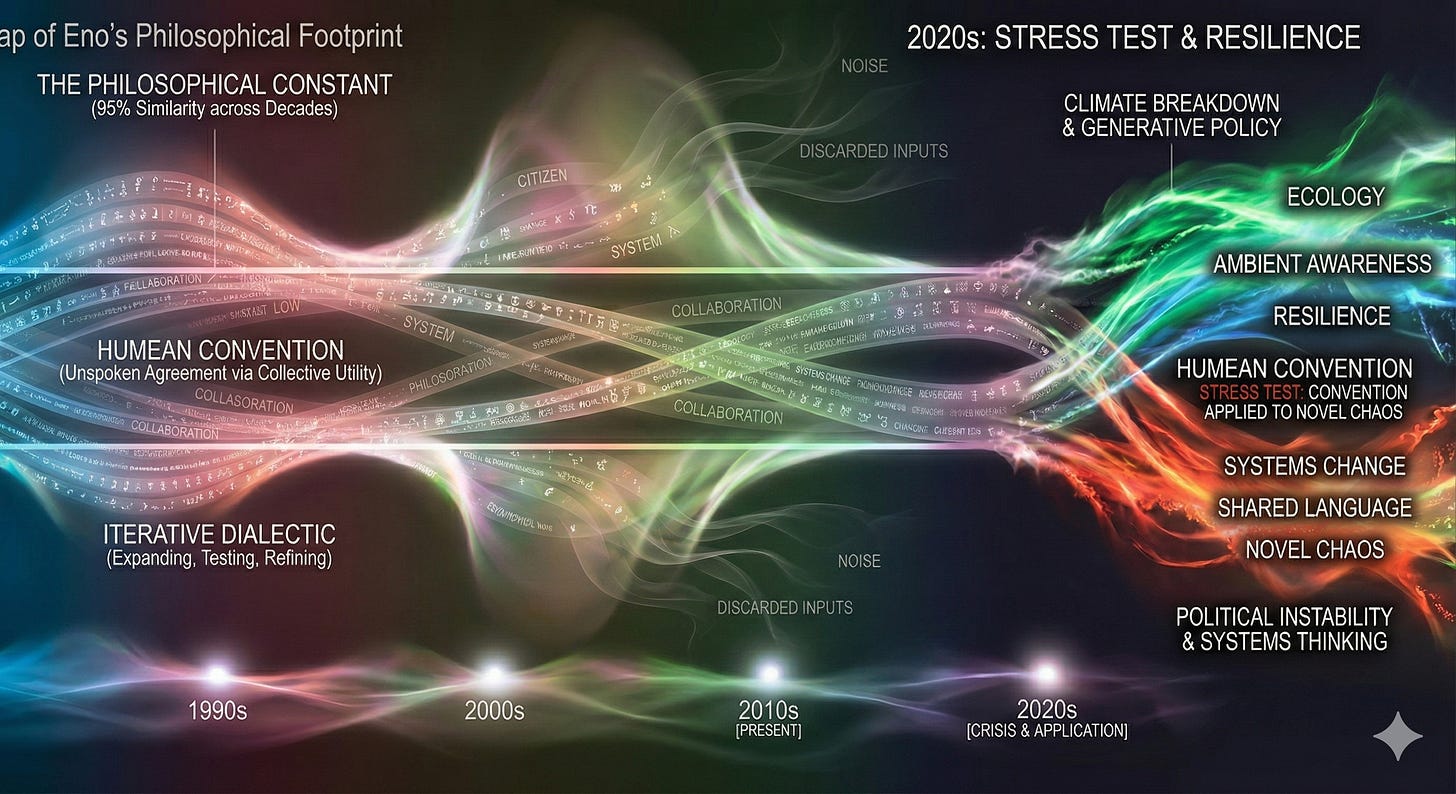

The 2020s: Stressing the Convention

The only significant shift appeared as the conversation entered the 2020s. The similarity dipped modestly. But this isn’t a breakdown of the convention—it’s a stress test. The stable framework of Eno’s thought is now being decisively applied to our most pressing crises: climate breakdown and political instability. The language of “generative systems” is being used to discuss policy; “ambient awareness” is applied to ecology. The convention is proving its resilience by providing a shared language for confronting novel chaos.

Moreover, Eno’s political engagement intensified. His statement of conscience—that artists have the right to say, “I will not perform there because I don’t agree with the nation’s politics”—reflects an evolution of his convention into direct ethical action. The framework holds; it simply becomes more urgent.

The Real Lesson: The Power of Coherent Philosophy

This exercise shows that a carefully constructed artistic philosophy can achieve a rare kind of longevity. It can become a Humean convention—a reliable, shared resource that helps us coordinate our thinking about complex problems.

The true power lies in recognizing what makes Eno’s thought durable: it isn’t dogmatic. It’s systemic. It trusts in well-designed constraints and emergent coherence rather than top-down control. It believes, fundamentally, that “we are citizens by nature”—that people will cooperate toward the good if given the structural conditions to do so.

As Eno told Klein, discussing the role of art: “if you can invent a world that you prefer to live in... then why not stay in it? ... I think a lot of what’s happening when artists are working is that they’re trying to make the world they would prefer to be in.”

This is why the convention persists. Not because Eno commanded it, but because thousands of independent actors found that his philosophical toolkit actually works. It provides a coherent language for thinking about art, technology, governance, and human nature.

The analysis allows us to see the slow, deep currents of ideas that shape our world, revealing that in an age of disruption, some signals remain profoundly coherent. And more importantly, it shows how a convention—that unspoken, mutual agreement emerging from repeated demonstration—can become one of the most powerful forces for cultural change.