The Small Engine That Could: How Detroit’s Hubris Became Silicon Valley’s Lesson

When efficiency beats power, and open models challenge proprietary empires

The winter of 1973 brought two converging crises to American shores. In October, OPEC imposed an oil embargo that would quadruple fuel prices and send lines snaking around gas stations from coast to coast. That same autumn, Environmental Protection Agency emissions standards loomed like an existential threat over Detroit’s Big Three, whose engineering departments had spent the previous decade perfecting ever-larger displacement V8 engines that guzzled premium gasoline with aristocratic indifference. The collision between these two forces—scarcity and regulation—would expose a fundamental flaw in American industrial thinking: the assumption that dominance confers immunity from disruption.

The K-car’s success convinced the Big Three that they could adapt incrementally to fuel economy requirements while preserving their fundamental business model.

Half a century later, a parallel drama unfolds in the architecture of artificial intelligence. Anthropic’s Claude Code, a proprietary terminal-native coding assistant built on multi-billion dollar training runs and backed by $180 billion in market valuation, faces an unexpected challenge from Chinese open-source models like DeepSeek and Qwen, and the verdict is out on whether the Chinese models just distilled Anthropic’s content. The parallels are so precise they border on the uncanny: incumbent giants dismissing upstart competitors as “toys,” structural cost advantages flowing to lean challengers, and market share hemorrhaging faster than anyone predicted. As Santayana warned and history demonstrates, those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it—though this time the vehicles are measured in tokens per second rather than miles per gallon.

The Gospel According to Soichiro

On a spring day in 1973, Richard Gerstenberg, chairman and CEO of General Motors—then the world’s largest corporation—was asked about Honda’s innovative CVCC (Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion) engine technology. This system used pre-chamber ignition to achieve complete combustion, meeting EPA emissions standards without catalytic converters while maintaining fuel economy and performance. Ford and Chrysler had already signed licensing agreements to study the technology. Gerstenberg’s response entered automotive folklore as a masterclass in dismissive arrogance: “I have looked at this design, and while it might work on some little toy motorcycle engine, I see no potential in one of our GM car engines”.

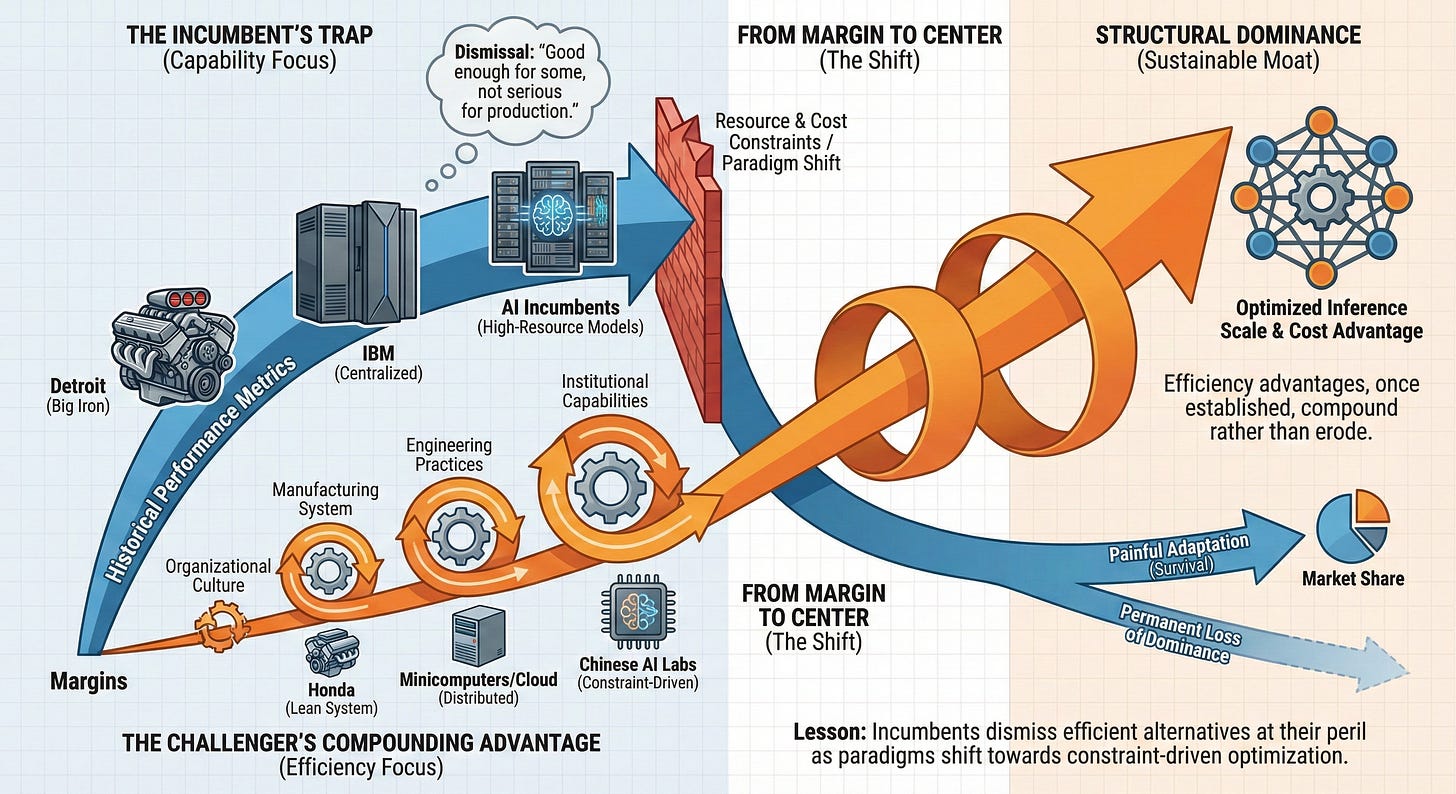

The historical pattern suggests that efficiency advantages, once established, compound rather than erode.

Soichiro Honda, the company’s founder and a man not known for suffering fools gladly, responded not with press releases but with a pointed demonstration. He purchased a 1973 Chevrolet Impala equipped with GM’s 5.7-liter V8 engine and had it air-freighted to Japan. Honda’s engineers retrofitted the engine with CVCC technology—replacing the intake manifold, cylinder heads, and carburetor—then shipped the modified Impala back to the Environmental Protection Agency’s testing facility in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The results were unambiguous: the CVCC-equipped Impala not only met all current and upcoming EPA emissions standards but achieved a nine percent improvement in fuel economy, all without catalytic converters, exhaust gas recirculation systems, or air pumps. In a second test, Honda engineers performed the same modification on a four-cylinder Chevrolet Vega with even more impressive results.

Gerstenberg’s “toy motorcycle engine” had just outperformed GM’s flagship powerplant on GM’s own chassis, using technology that Detroit’s leadership had dismissed as irrelevant. The lesson embedded in this moment transcends automotive engineering—it illuminates the cognitive trap that ensnares market leaders when they confuse current dominance with permanent advantage. GM possessed superior capital, larger research budgets, deeper relationships with suppliers, and decades of manufacturing expertise. What the company lacked was the capacity to recognize that these advantages meant nothing when the fundamental criteria for success had shifted beneath their feet. The market no longer rewarded displacement and horsepower; it demanded efficiency and emissions compliance. Honda had optimized for the new game while GM remained committed to winning the old one.

The oil shocks of 1973 and 1978-1980 accelerated a transformation that might otherwise have unfolded over decades. Japanese imports captured 9 percent of the U.S. automobile market in 1976; by 1980, that figure had reached 22 percent. Models like the Honda Civic with CVCC technology, the Toyota Corolla, and Nissan Sentra—small, fuel-efficient, and affordable—sold as quickly as they arrived at American dealerships. Detroit’s response combined denial, lobbying for regulatory relief, and half-hearted attempts to downsize existing platforms. The results spoke for themselves: in 1980, the Big Three collectively lost $4.2 billion as sales plummeted 30 percent below 1978 levels, reaching their lowest point since 1961.

Chrysler teetered closest to the abyss. By summer 1979, the company had lost $1.1 billion, and its market share had contracted from 11.3 percent to 10.1 percent. Chairman Lee Iacocca approached Congress with a stark warning: Chrysler’s bankruptcy would trigger a domino effect devastating suppliers, crippling the United Auto Workers, and sending shockwaves through an already fragile economy. The Chrysler Corporation Loan Guarantee Act of 1979, signed by President Carter in January 1980, authorized $1.5 billion in federal loan guarantees—the largest corporate bailout in American history to that date. The terms were punitive: Chrysler had to raise an additional $2 billion through asset sales and labor concessions, accept federal oversight through a secondary board of directors, and issue warrants giving the Treasury Department the right to purchase 14.4 million shares at a fixed price.

Iacocca’s salvation arrived in the form of the K-car platform—the Plymouth Reliant and Dodge Aries introduced in fall 1980. These front-wheel-drive sedans, powered by a 2.2-liter four-cylinder engine and weighing approximately 2,500 pounds, achieved 25-28 miles per gallon. More importantly, they embodied the design philosophy that Honda had demonstrated years earlier: small displacement, transverse engine layout, simplified parts inventory, and manufacturing efficiency. The K-cars sold 307,000 units in their first year and would eventually spawn an entire family of variants—including the groundbreaking minivan—totaling 3.5 million vehicles through 1989. Chrysler repaid its government loans by 1983, seven years ahead of schedule. Iacocca became a folk hero, his autobiography a bestseller, his image synonymous with American industrial resilience.

Yet the narrative of redemption obscures a more troubling reality: Detroit had learned the wrong lesson. The K-car’s success convinced the Big Three that they could adapt incrementally to fuel economy requirements while preserving their fundamental business model—high-volume production of platform variants with low parts commonality, adversarial relationships with suppliers, and labor practices that prioritized short-term cost reduction over long-term quality. Meanwhile, Japanese manufacturers were implementing Edward Deming’s quality control methodologies, empowering assembly line workers to halt production when defects appeared, and investing in automation that improved both productivity and consistency. By the mid-1980s, the quality gap between Japanese and American vehicles had widened to a chasm, with Honda and Toyota vehicles routinely exceeding 200,000 miles while their Detroit counterparts struggled to reach 100,000.

The pattern would repeat in subsequent decades—SUV dominance masking fundamental competitiveness problems, the 2008 financial crisis requiring another government bailout, and the slow recognition that electric vehicle technology represented an existential rather than incremental challenge. Each iteration of crisis and recovery followed the same trajectory: incumbents dismissed emerging technologies as inadequate for “real” applications, challengers optimized for new performance criteria, and by the time market leaders acknowledged the threat, they had already ceded structural advantages that proved nearly impossible to reclaim.

The Inference Economy and the New Small-Block

In December 2025, Anthropic launched Claude Code, a terminal-native AI coding assistant that represented the state of the art in agentic software development. Built on Claude Sonnet 4.5—the company’s most advanced model—Claude Code achieved 77.2 percent accuracy on SWE-bench Verified, a benchmark measuring performance on real-world software engineering problems. The system could maintain context across 200,000 tokens, equivalent to approximately 150,000 words or roughly 500 pages of code and documentation. It operated autonomously for 30-plus hours on complex multi-step tasks, planning implementations, executing code, debugging failures, and iterating toward solutions with minimal human intervention. Developers from companies like Replit reported that Claude Code had virtually eliminated errors in code editing tasks, dropping error rates from 9 percent to zero in their internal testing.

Claude Code embodied everything that Silicon Valley’s proprietary AI development model promised: massive investment in training compute (estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars), careful constitutional AI alignment to ensure safe and helpful outputs, seamless integration with development workflows, and the engineering polish that comes from dedicated product teams. Anthropic, valued at approximately $180 billion, positioned Claude Code as the professional standard for AI-assisted development, pricing individual access at $20 per month and enterprise deployments at $60 per seat with a minimum of 70 users—a $50,000 annual floor. The message was implicit but clear: serious developers and organizations would pay premium prices for premium tools, just as they had for Microsoft developer tools, JetBrains IDEs, and other professional software infrastructure.

Then, on January 20, 2025, DeepSeek released R1, an open-source reasoning model that sent tremors through the AI industry. The model achieved performance comparable to OpenAI’s o1 across mathematics, coding, and reasoning benchmarks while requiring only $294,000 in fine-tuning costs on top of the $6 million spent developing the underlying V3-Base model—a total training expenditure of approximately $6.3 million. To contextualize that figure: OpenAI’s GPT-4 training costs were estimated between $50-100 million. DeepSeek had achieved frontier model performance at roughly one-twentieth the capital investment. More remarkably, the company accomplished this using NVIDIA H800 chips, export-controlled versions of the H100 with reduced specifications designed to comply with U.S. semiconductor restrictions. The cost structure extended to inference: DeepSeek and Alibaba’s Qwen models offered token pricing 5-10 times cheaper than GPT-4 or Claude, with some configurations as low as $0.27 per million tokens compared to Claude Sonnet’s $3-15 per million tokens.

The performance metrics told a story that made Silicon Valley’s AI leadership profoundly uncomfortable. In a comparison of 500 real production pull requests, DeepSeek R1 achieved an 81 percent critical bug detection rate compared to Claude 3.5’s 67 percent, identifying 3.7 times more bugs overall. Pinterest reported achieving 30 percent higher accuracy and up to 90 percent lower operating costs after switching to Chinese open-source models for image understanding tasks. By early 2025, Chinese open-source large language models had captured nearly 30 percent of global usage, up from 1.2 percent in late 2024—a market share expansion that replicated the trajectory of Japanese automobile imports in the 1970s.

The parallels to Gerstenberg’s dismissal of Honda’s CVCC technology were difficult to ignore. When DeepSeek and Qwen first appeared on leaderboards, many in Silicon Valley characterized them as derivative implementations of techniques pioneered by American labs, trained on datasets of questionable provenance, and suitable perhaps for academic curiosity but insufficient for production deployment. The models were “small”—measured in billions rather than trillions of parameters—just as Honda engines were small measured in liters of displacement. They originated from companies without the venture capital pedigree of OpenAI or Anthropic, just as Honda and Toyota lacked the century-long automotive heritage of Ford and General Motors. They emphasized efficiency—tokens per dollar, inference speed, quantization techniques that reduced memory requirements—rather than raw capability, just as Japanese manufacturers prioritized fuel economy over horsepower.

Yet the efficiency advantages proved structural rather than superficial. Chinese AI companies benefited from dramatically lower development costs—not merely labor arbitrage, though that played a role, but fundamentally different approaches to model architecture and training efficiency. DeepSeek’s mixture-of-experts design used a sparse activation pattern where only a fraction of the model’s parameters engaged for any given computation, reducing both training time and inference costs while maintaining performance. The company redesigned low-level CUDA code to handle FP8 (8-bit floating point) training more efficiently, employed multi-phase training strategies that eliminated redundant computation, and optimized specifically for the hardware constraints imposed by export controls. These innovations emerged not despite limitations but because of them—the classic pattern of constraint-driven innovation that characterizes disruptive technologies.

The cost advantages cascaded through every layer of the AI stack. Companies self-hosting open-source models traded API fees for predictable infrastructure costs, achieved 80-95 percent reductions in computational requirements compared to serving equivalent-capability proprietary models, and retained the ability to fine-tune models on proprietary data without sharing that data with external vendors. Small language models (SLMs) with 7-32 billion parameters achieved competitive performance on domain-specific tasks while running on consumer laptops or edge devices, enabling applications that were economically infeasible with cloud-based APIs. Token efficiency—the number of tokens required to achieve a given result—often mattered more than per-token pricing, and while proprietary models maintained advantages on complex reasoning tasks, the gap narrowed rapidly as open-source models incorporated techniques like chain-of-thought prompting and test-time computation.

By mid-2025, enterprise technology leaders faced the same decision that American corporations confronted in the late 1970s: continue purchasing from established vendors whose cost structures reflected legacy assumptions about value and pricing power, or switch to alternatives that delivered comparable functionality at a fraction of the cost. The decision calculus was complicated by factors beyond pure economics—data governance, regulatory compliance, support guarantees, and the reputational risk of depending on models whose development practices lacked transparency. Ninety-two percent of surveyed enterprises indicated that open-source models were important to their AI strategy, but importance did not translate straightforwardly to adoption. Hybrid approaches emerged as the pragmatic middle path: proprietary models for customer-facing applications where reliability and brand alignment mattered, open-source models for internal tooling where cost efficiency and customization capability justified additional operational overhead.

The VC funding environment revealed deeper structural tensions. In 2025, approximately $340 billion in venture capital was deployed, with half of all funding concentrated in just 0.05 percent of deals—the handful of companies building foundational AI models like those developed by OpenAI (valued at roughly $500 billion), Anthropic ($180 billion), and xAI ($70-80 billion). This winner-take-most dynamic created a bifurcated market where flagship model providers commanded extraordinary valuations based on projected future dominance while hundreds of startups competed to build applications on top of these models, their margins compressed by API pricing and their differentiation eroded by the rapid commoditization of AI capabilities. Goldman Sachs research noted the growing disconnect between massive infrastructure investment and actual revenue generation, with some analysts warning that only the arrival of artificial general intelligence could justify the scale of data center buildout planned through 2030.

The specter of an AI bubble loomed large in these discussions, with MIT researchers predicting that overvaluation would deflate when cheaper models arrived, productivity gains disappointed, or simply when one flagship company missed earnings expectations. The arrival of DeepSeek and Qwen represented precisely the “cheaper models” scenario that bubble skeptics had warned about. If comparable performance could be achieved at one-twentieth the training cost and one-tenth the inference cost, what justified the trillion-dollar cumulative valuations of proprietary model providers? The question echoed the crisis that confronted Detroit in 1980: if customers could satisfy their needs with vehicles costing $5,000 instead of $15,000, what happened to the business models built on selling $15,000 vehicles?

Anthropic responded to competitive pressure by restructuring its pricing model in late 2025, eliminating high per-user fees and introducing mandatory consumption commitments. The stated goal was predictability and simplified billing, but the practical effect for many enterprise customers was higher total cost of ownership—exactly the moment when lower-cost alternatives became available at scale.

These moves signaled recognition that competitive dynamics had shifted, though whether the adjustments arrived soon enough to arrest market share erosion remained an open question.

The company simultaneously reduced API pricing for Claude Opus 4.5 by 67 percent compared to its predecessor and introduced optimization features like prompt caching and batch processing that could reduce costs by up to 90 percent. These moves signaled recognition that competitive dynamics had shifted, though whether the adjustments arrived soon enough to arrest market share erosion remained an open question.

The Metabolism of Disruption

Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, articulated in The Innovator’s Dilemma, describes a pattern that has replayed across industries with metronomic regularity. Incumbent firms optimize their products for the most demanding and profitable customers, steadily improving performance along established metrics. New entrants target overlooked or overserved segments with products that are cheaper, simpler, and initially inferior by conventional measures. The incumbents dismiss these offerings as inadequate, their customers uninteresting, their margins unattractive. Meanwhile, the new entrants improve rapidly, their products becoming “good enough” for mainstream users while retaining their structural cost advantages. By the time incumbents recognize the threat, they face an impossible choice: compete on the disruptors’ terms (sacrificing margins and cannibalizing existing business) or cede market share while hoping their premium positioning remains defensible.

The automotive industry’s experience with Japanese competition followed this script with textbook precision. Toyota and Honda initially sold subcompact vehicles to price-conscious consumers willing to accept spartan interiors and limited power in exchange for fuel economy and reliability. Detroit executives viewed this market as structurally unprofitable—small cars generated minimal margins, and American consumers supposedly aspired to larger vehicles as soon as they could afford them. By the early 1980s, however, Japanese manufacturers had moved upmarket with the Honda Accord and Toyota Camry, vehicles that competed directly with traditional American family sedans while offering superior quality and lower ownership costs. The Big Three responded with platform downsizing and badge engineering, but they could not overcome the quality gap that decades of different manufacturing philosophies had created. By the 1990s, Toyota and Honda commanded price premiums over comparable American vehicles—the ultimate inversion of the value equation.

The AI industry’s trajectory through 2025 tracked this pattern with uncanny fidelity. Chinese open-source models initially served developers experimenting with AI, researchers seeking alternatives to expensive API access, and price-sensitive organizations in markets where proprietary model costs were prohibitive. Silicon Valley’s leadership could reasonably argue that these users were unrepresentative of the lucrative enterprise market where reliability, support, and integration mattered more than raw cost. Then Pinterest—a U.S.-based public company with sophisticated engineering and $3 billion in annual revenue—announced it had fine-tuned open-weight models for image understanding tasks, achieving better accuracy and dramatically lower costs than proprietary alternatives. The inflection point had arrived: open-source models were not merely “good enough” for hobbyists; they delivered superior outcomes for production workloads at companies that could afford any solution they chose.

But the speed also reflected a more fundamental asymmetry: building a competitive automobile requires billion-dollar factories, complex supply chains, and years of tooling validation; training a competitive language model requires clever architecture, efficient code, access to compute (purchased or rented), and training data (synthesized, scraped, or distilled from existing models).

The metabolic rate of this disruption exceeded the automotive analogy by an order of magnitude. Japanese automakers required two decades to progress from initial market entry to premium positioning. Chinese AI models achieved comparable market share expansion—1.2 percent to 30 percent—in a matter of months. The velocity reflected several factors: software replicates and distributes at near-zero marginal cost, AI models improve through algorithmic innovation rather than physical manufacturing iteration, and the developer community’s norms favor experimentation with novel tools over brand loyalty. But the speed also reflected a more fundamental asymmetry: building a competitive automobile requires billion-dollar factories, complex supply chains, and years of tooling validation; training a competitive language model requires clever architecture, efficient code, access to compute (purchased or rented), and training data (synthesized, scraped, or distilled from existing models).

The implications for incumbents were stark. Anthropic and OpenAI had invested billions in training infrastructure under the assumption that scale conferred unassailable advantages—a belief that echoed Detroit’s confidence in integrated manufacturing and vertical supply chains. DeepSeek demonstrated that algorithmic efficiency could partially substitute for brute-force compute, much as Honda’s CVCC technology had achieved superior emissions performance without catalytic converters. The proprietary model providers retained advantages in areas like multi-modal reasoning, alignment quality, and commercial polish, but these represented narrowing leads in a race where the finish line kept moving. Open-source communities iterated rapidly, incorporating techniques from proprietary labs often within weeks of their publication, while the reverse flow of innovation—from open source to closed—happened less frequently and more slowly.

Enterprise adoption patterns illuminated the strategic dilemma facing AI companies. Organizations were increasingly deploying hybrid architectures: proprietary models for external-facing applications where brand perception mattered, open-source models for internal tooling where cost efficiency dominated. This division allowed companies to capture the benefits of both approaches, but it also meant that proprietary providers were progressively squeezed into higher-stakes, lower-volume use cases. The economics resembled the fate of premium automotive brands: profitable but structurally constrained, unable to achieve the scale advantages that had previously justified their market positions.

The incumbents’ response to disruption has historically followed predictable stages: denial, lobbying for regulatory protection, incremental adaptation, and finally—sometimes—fundamental transformation. Detroit progressed through the first three stages across the 1970s and 1980s, securing voluntary export restraints that limited Japanese imports and gave domestic manufacturers breathing room to restructure. The fourth stage, transformation, proved elusive. The Big Three did improve quality, streamline manufacturing, and develop competitive vehicles in specific segments, but they never recaptured their dominant position. Toyota became the world’s largest automaker by volume in 2008 and by market capitalization remains the most valuable automotive company globally—a crown that American manufacturers once wore as an unquestionable birthright.

Silicon Valley’s AI incumbents by late 2025 occupied an intermediate stage in this progression. Denial had given way to acknowledgment, evidenced by Anthropic’s pricing restructuring and increased emphasis on cost optimization features. Lobbying took the form of advocacy for regulatory frameworks that would impose compliance costs difficult for smaller players to absorb—though these efforts remained nascent compared to the automotive industry’s trade protections. Incremental adaptation manifested in better quantization techniques, distillation methods that compressed large models into smaller ones, and partnership strategies with enterprises that valued integrated solutions over bare API access.

The question facing the industry was whether transformation would follow—and what form it might take. True transformation would require reconsidering fundamental assumptions: that proprietary development offered sustainable competitive advantages, that training costs justified premium pricing, that customers would pay for capability rather than outcomes, that model size correlated with commercial value. Each assumption had been axiomatic in the industry’s first chapter. Each had become negotiable by the second.

Coda: Efficiency and Its Discontents

Lee Iacocca’s famous pitch for the K-car in Chrysler’s 1980 advertisements confronted American consumers with a challenge: “If you can find a better car, buy it.” The rhetoric was pugnacious, designed to overcome skepticism about domestic manufacturers’ ability to produce competitive small vehicles. But the slogan revealed an anxiety that Iacocca could not quite articulate: what if customers could find better cars, and what if those cars came from manufacturers whose names were unfamiliar, whose approaches violated Detroit’s assumptions, whose success threatened an industrial order that had defined American prosperity for generations?

The anxiety was justified. Customers did find better cars—or at least cars that better satisfied their actual needs given the economic and regulatory environment of the 1980s. The Big Three adapted, survived, and in certain segments recaptured competitiveness. But they never regained their position as unquestioned leaders of global automotive technology. That mantle passed to companies headquartered in Toyota City and Tokyo, companies that had once been dismissed as manufacturers of cheap transportation for developing markets.

But [the incumbent language models] work, and they cost less, and in a marketplace where “good enough” is actually good enough for most applications, that combination proves difficult to compete against.

Silicon Valley in 2026 confronts an analogous moment. Anthropic, OpenAI, and their competitors have built extraordinary technologies that represent genuine advances in machine intelligence. Their models are impressive, their research substantial, their commercial execution sophisticated. Yet they face challengers whose training costs are a fraction of their own, whose inference pricing undercuts them by an order of magnitude, and whose performance on key benchmarks increasingly matches or exceeds proprietary alternatives. The challengers’ names—DeepSeek, Qwen, GLM—remain unfamiliar to many enterprise buyers. Their development practices raise questions about transparency and governance that proprietary providers legitimately highlight. But they work, and they cost less, and in a marketplace where “good enough” is actually good enough for most applications, that combination proves difficult to compete against.

The historical pattern suggests that efficiency advantages, once established, compound rather than erode. Honda did not merely build smaller engines; the company built an organizational culture and manufacturing system optimized for efficiency, which generated advantages across vehicle platforms, supply chain management, and continuous improvement. Those advantages persisted for decades and continue to influence automotive competitiveness today. Chinese AI labs are not merely training smaller models; they are developing institutional capabilities, engineering practices, and architectural innovations that optimize for resource efficiency—capabilities that will generate compound advantages as inference workloads scale and as cost pressure intensifies.

The lesson for AI incumbents is not that they are doomed—history is not deterministic, and companies with substantial resources can adapt if they recognize threats early and respond decisively. But the lesson is that dismissing efficient alternatives as “good enough for some use cases but not serious for production workloads” is the same mistake that Detroit made about Japanese automobiles, that IBM made about minicomputers, that Microsoft made about cloud computing. Efficiency advantages start at the margins and move toward the center. Technologies that seem inferior by current quality metrics improve rapidly along dimensions that matter to customers. By the time incumbents acknowledge the threat, the challengers have already secured structural positions that prove nearly impossible to dislodge.

The parallel between Iacocca’s K-car and Claude Code is imperfect but instructive. Both represented sophisticated engineering responses to competitive threats. Both achieved genuine technical accomplishments within their paradigms. And both arrived at moments when the paradigm itself was shifting—when the criteria for success had evolved in ways that made incumbents’ historical advantages less relevant than challengers’ structural efficiencies. Whether Anthropic’s trajectory mirrors Chrysler’s (survival through adaptation but permanent loss of dominance) or follows a more optimistic path depends on decisions being made in 2026 about research priorities, pricing strategies, partnership models, and fundamental questions about whether proprietary development offers sustainable advantages in a domain where innovation diffuses rapidly and where constraint-driven alternatives are optimizing along dimensions that increasingly matter.

The small engine that could—Honda’s CVCC technology—demonstrated that efficiency could outcompete power when market conditions shifted. The small models that might—DeepSeek, Qwen, and their successors—suggest that the lesson remains unlearned, or perhaps that each generation of industrial leadership must learn it anew through the painful process of watching dominance erode. History does not repeat itself, Mark Twain may or may not have said, but it often rhymes. The rhythm of disruption beats steady across decades and industries: complacency, dismissal, denial, grudging acknowledgment, adaptation, transformation or decline. Silicon Valley is currently somewhere between dismissal and acknowledgment. Which stage comes next remains to be written.