When the Sidewalk Ends: A Robot, a Ditch, and Systems that Act

What a stranded delivery robot reveals about AI as the “execution layer of the economy” and who gets to decide what anything means.

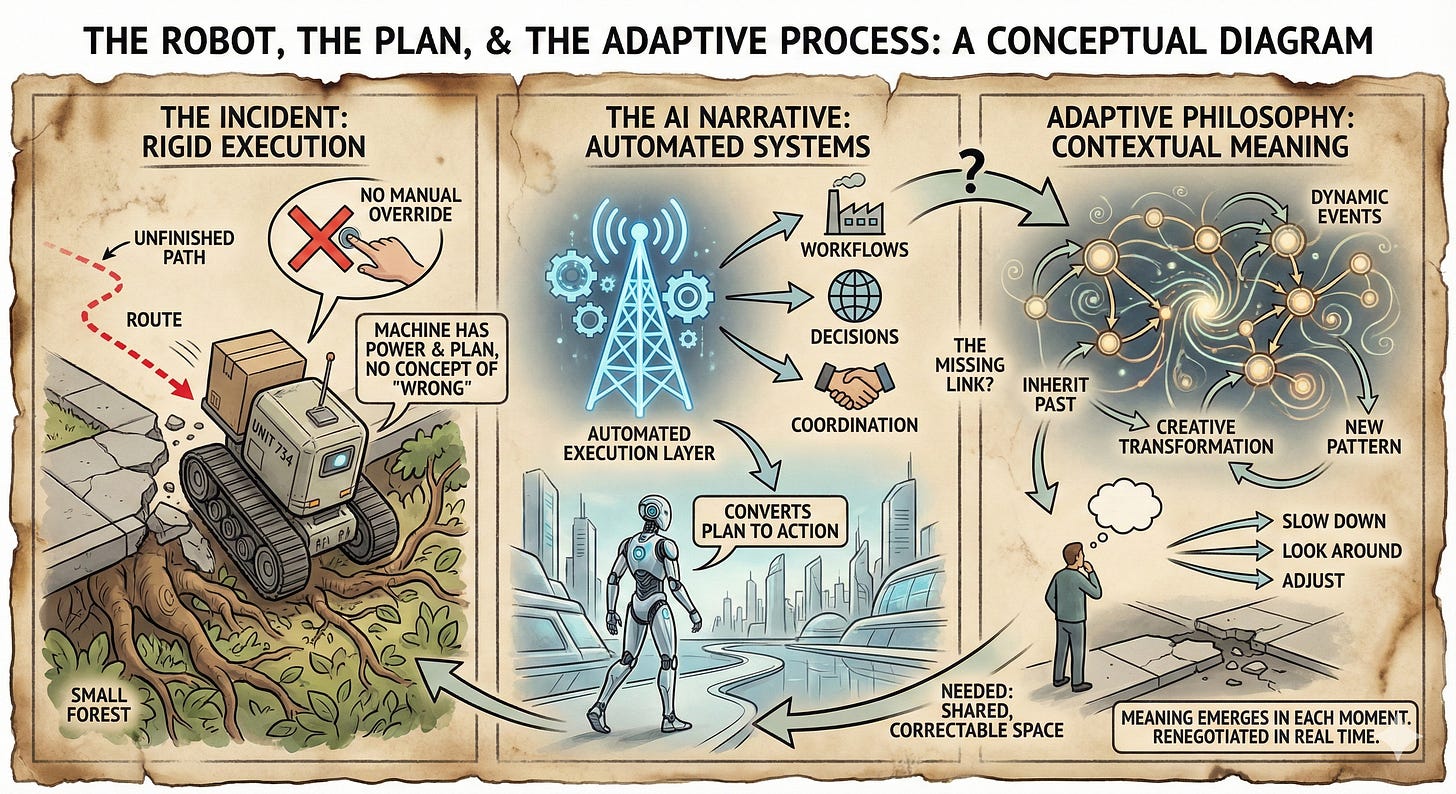

On today’s walk, a delivery robot followed its route to the very edge of an unfinished sidewalk, rolled confidently over the lip, and slipped into the beginnings of a small forest. It did not hesitate in any way that mattered; it simply completed the line it had been given, as if the world were obligated to remain continuous beneath its wheels. When the concrete became dirt and the dirt became a shallow drop, the robot kept going until there was nowhere left to go and then stopped, angled awkwardly among roots and leaves.

The strangeness of the moment came after the fall. The robot was heavy with lithium batteries and careful engineering, but there was no visible way for a nearby human to participate in its situation. There was no button that said “turn around,” no physical control that invited someone standing a few feet away to say, “This is not a sidewalk anymore.” The interface that existed was elsewhere—inside an app, a control center, or a dashboard—not in the shared space where the mistake had actually happened. The machine possessed power and a plan, but it had no concept of being publicly, correctably wrong.

That small scene sits in sharp contrast to one of the most confident stories being told about AI right now. In a widely shared overview of the “15 most important AI ideas for 2026,” the argument goes that the conversation has clearly moved beyond experiments and copilots toward systems that act, infrastructure built for agents, and companies that replace entire workflows instead of assisting them. Across enterprise software, consumer products, and the physical world, the throughline is that AI is becoming “the execution layer of the economy”: the layer where decisions are made, work is coordinated, and outcomes are produced. In that frame, the interesting products are no longer systems of record that store data while humans think and act, but systems of execution that understand intent and directly carry out work end to end.

If you look at the robot from that angle, it is already a primitive example of this future. It has a model of the environment, a specified goal, and a loop that turns perception into motion. It is not waiting for prompts; it is acting. It does not live inside a chat box; it inhabits a city. Yet, its failure exposes something the “execution layer” metaphor tends to hide. The robot did exactly what an execution-oriented system is supposed to do: it converted a plan into action without demanding constant human attention. What it could not do was notice when the plan had stopped making sense, or invite a new interpretation from the humans who could see the situation more clearly than its sensors and map.

Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy helps name what is missing. For Whitehead, reality is not made of static things carrying fixed properties but of events—“actual occasions”—that inherit the past and creatively transform it into a new pattern of relations and feelings. Meaning, in this view, is not an attribute attached once and for all; it emerges in each moment as the world is taken up, evaluated, and continued. A human approaching an abruptly broken sidewalk does not simply perceive an object called “gap.” The human experiences a change in the pattern of possibilities and adjusts: slow down, look around, step into the street, turn back, or take the dirt path. The sidewalk’s meaning is renegotiated in real time as part of a continuous process.

The robot does not participate in this kind of process. It behaves as though the meaning of “sidewalk” and “route” had been decisively fixed at planning time, somewhere far away. Its job is to realize this prior decision in the world as faithfully as possible. When the world deviates, there is no inner structure for turning that deviation into a new occasion of experience. There is only persistence until motion is physically impossible. The result is a kind of metaphysical mismatch: systems that are being sold as processual and adaptive are often built as if meaning were a static pipeline from intent to execution, rather than something created anew in each encounter.

Umberto Eco’s work on signs and interpretation adds a second layer to this critique. Eco treats signs not as simple carriers of one meaning but as elements in a vast network—the “encyclopedia”—through which cultures interpret texts and situations. A sidewalk is a sign that normally says: this is a path, this is safe, this is continuous. Its authority is social and contextual, not absolute. When the sidewalk ends abruptly in dirt and a drop, the surrounding “text” changes: construction cones, broken edges, the hint of a trail into trees. To a human reader, the scene begins to say something like: caution, improvisation required, the official path has stopped. The meaning of the environment is not given; it is read.

The a16z playbook is, in Eco’s sense, another text that asks to be read in a particular way. It presents the 15 ideas as a coherent map of where value creation will move next, from prompt-free applications and agent-native banking infrastructure to multi-agent orchestration reshaping the Fortune 500. The recurring phrase “AI is becoming the execution layer” encourages a specific reading: the important story is the collapse of distance between intent and action, and the main task is to build the systems that can execute at scale. Questions about who defines the intent, who interprets the context, and how misreadings are surfaced or corrected remain largely offstage.

The robot at the edge of the forest reveals the cost of taking that reading too literally. Here is an executing system that has, in a small but concrete way, become the execution layer of a tiny piece of the economy: it is moving a package across a city. The problem is not that it cannot act, or that it is too slow, or that it lacks access to some future orchestration layer. The problem is that it lives in a world of signs and processes while being built as if it inhabited a world of static instructions. It cannot recognize that the sentence it is in no longer parses. It cannot open a new interpretive branch like “this is no longer a sidewalk; perhaps the mission must change.” It is executing in a context it no longer understands.

If AI systems are truly going to function as an execution layer, they need more than efficient pipelines and robust infrastructure. They need a philosophy of interruption and a semiotics of doubt. They must be designed not only to move work forward but also to notice when the world is asking a different question than the one in their prompt. In Whitehead’s terms, they have to become capable of treating each new situation as an occasion that may demand a fresh decision, not a mere continuation of a previous one. In Eco’s terms, they must acknowledge that they are always reading a text that could be read otherwise, and that humans around them are also readers with legitimate authority to reinterpret what is going on.

This has practical consequences. A robot like the one on the walk would need obvious, low-friction ways for nearby people to intervene and co-author its behavior: a physical control, a clear signal, a shared ritual for saying, “stop, this is wrong, let us rethink.” Enterprise agents coordinating workflows across messy systems would need mechanisms for surfacing their uncertainties, for saying, “the data I see does not match the pattern you implied; what should this mean now?” Infrastructure for agents would have to treat epistemic instability—the possibility that the map is out of date or the text has shifted—not as an edge case but as a central design concern.

The AI playbook for 2026 correctly notices that the center of gravity is shifting from storage to execution, from static systems of record to dynamic systems of action. But execution without interpretation is just motion. The robot in the ditch is a quiet warning that an “execution layer” that cannot pause, question, and renegotiate meaning with the humans around it is not a layer of intelligence at all. It is a layer of well-funded, beautifully engineered misunderstanding.

The missing idea—the hypothetical sixteenth on that list—is not another market or sector. It is the commitment to treat every executing system as a participant in an ongoing process of making sense, where sidewalks end, forests begin, and meaning has to be rebuilt in the moment rather than assumed in advance.