How to Build Software that Withstands the Test of Time

What the Pantheon’s Oculus Can Teach Product Managers About Architecture in the Age of Generative Code

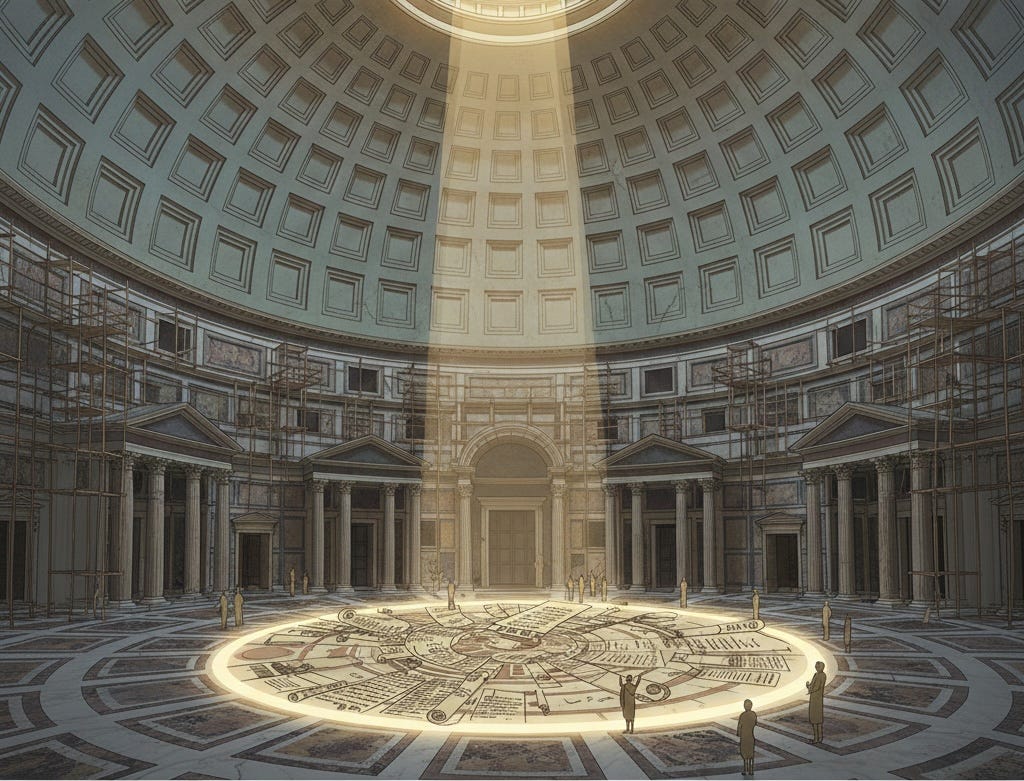

The Pantheon’s oculus has been throwing a perfectly ordinary circle of light onto a Roman floor for almost two thousand years, and we still argue about how, exactly, the whole structure was made to stand. We know a lot: Roman concrete mixed with volcanic ash, the stepped thinning of the dome, lighter aggregates as you rise, the coffering that cuts weight without giving up presence, and the oculus itself acting as a compression ring that both relieves mass and stabilizes the span. We can model scaffolds, wood formwork, brick “bipedales” locked into the ring, and the way weight moves down into that improbably thick cylindrical drum. What we do not have is the full record of the arguments, iterations, and guild‑level corrections that turned a risky drawing into a dome that has not collapsed, despite never having seen a rebar truck. The Pantheon sits there as a live refutation of the idea that you can separate technique from apprenticeship, or structural ambition from the social systems that decide who is allowed to touch the design.

Guilds, not gladiators

Medieval craft guilds were, among other things, a technology for regulating who was allowed to make which mistakes. Apprentices spent years on the simplest tasks—quarrying, cutting, carrying—before touching anything that could bring down a roof; journeymen moved inside the logic of joints and spans; masters took formal responsibility for structures whose failure would be recorded in stone and law, not just in a bug tracker. Guilds controlled access to tools and trade secrets, enforced standards, and required a “masterpiece” as a proof that someone could design as well as execute before they were trusted with a whole commission. That slowed certain forms of innovation and entrenched monopolies, but it also meant the riskiest decisions were made by people who had seen enough failures to internalize what was actually at stake. The point was not to romanticize hierarchy; it was to make sure the person sketching the dome understood what a crack meant for the people standing underneath.

Current AI‑native software practice often inverts that logic. Generative coding tools like Claude and others can now produce convincing architectures—service meshes, plugin systems, orchestration layers—that look, on first pass, like something a seasoned engineer might design. The interface collapses apprenticeship: a new hire or overstretched product manager can sit down, request a pattern, and get a fully annotated answer, without the years of slow feedback that normally carve structural intuition into a person’s nervous system. In principle, this is an extraordinary expansion of access. In practice, when organizations do not build explicit review loops on top of these tools, they end up with what looks like master‑level work designed by a system that has never been forced to live with the consequences of its own plans. The guild function—sequencing exposure to risk, enforcing standards, connecting design authority to lived accountability—gets dissolved into a flat landscape where everyone can, in theory, draw a dome.

Vibe coding without feedback is not architecture

The “SaaS‑copalypse” debate tends to oscillate between panic and triumphalism: either white‑collar software work is about to be swallowed by AI, or we are entering an age of infinite leverage and solo founders. Both stories miss the same point. What matters is less who types the code and more how feedback from real systems, over real time, is allowed to shape the patterns that survive. Vibe coding—at individual or enterprise scale—means accepting outputs that feel coherent in the editor, in a demo, or in the first week of load, without a disciplined practice of relating them back to incidents, edge cases, and the slow emergence of cross‑cutting constraints. If the only feedback loop is “did it run” and “does the dashboard look green right now,” architecture becomes an aesthetic, not a discipline.

For product managers trying to do more than ride hype, this is the actual danger. The combination of tight deadlines, cheap generative tools, and top‑down pressure to “move fast on AI” incentivizes shipping architectures that nobody really owns, because nobody has time to trace their behavior beyond the current quarter. In that environment, junior developers and models are both asked to perform master‑level design work without the guardrails guild systems used to provide. The apprenticeship layer—where someone learns over years which abstractions deform gracefully under new requirements and which ones shatter—gets eaten for margin. What looks, from the outside, like a productivity boom can feel, from inside the stack, like building a dome whose cracks will only appear once most of the original team has moved on.

Es Devlin’s libraries and the ethics of encounter

Es Devlin’s “Library of Us” installation in Miami made a different proposal for how complex systems might hold many minds at once. The work stages thousands of books on a revolving structure, with readers seated at a circular table while shelves glide past their field of view; if you sit long enough, the same texts and people return, slightly shifted, offering another chance to pick up a conversation where you left off. Devlin has described libraries as “silent, intensely vibrant places where minds and imaginations soar, while clutched like kites by their seated bodies,” spaces where you can feel “a temporary community of readers” forming as ideas circulate. The books from the installation are later dispersed into public libraries and schools, each marked with a small circular hole—a trace of the structure they once held together, and a reminder that architectures can leave residues in the objects and people that pass through them.

That is one way to think about the work of product and platform teams in the age of AI. Tools like Claude are not just code generators; they are mechanisms for orchestrating encounters—between users and interfaces, between data and decisions, between different theories of what a system is for. A well‑designed architecture is less like a static building and more like Devlin’s rotating library: a structure that choreographs who is likely to meet which ideas, and under what terms. This is where philosophy stops being decoration. Thinkers like Umberto Eco, who treated libraries as models of open‑ended interpretation, or Alfred North Whitehead, who framed civilization as the slow accumulation of “operations we do not have to think about,” are pointing at the same design question from different angles: which operations will your system silently normalize, and whose agency will be shaped by those defaults. When AI becomes the execution layer, architecture becomes a form of applied ethics.

What it means to be an oculus builder

For product managers who do not want to become hype followers, the oculus is a better aspiration than the demo. The oculus is the part of the dome that looks like pure absence—an opening—but functions structurally as a compression ring and symbolically as a way of admitting light and weather into a controlled space. It is a reminder that sometimes the most important architectural choice is what you refuse to fill: which features you do not automate, which decisions you do not outsource to a model, which responsibilities you insist remain legibly human, even if the tooling could absorb them. In a culture wired for “ship more,” leaving an oculus in the system—a deliberate gap where judgment, review, or collective deliberation must pass—can feel like heresy. Historically, it has also been one of the few reliable ways to keep structures from collapsing under the weight of their own cleverness.

Practically, that means a few unglamorous commitments. It means building guild‑like paths inside organizations, where exposure to AI tooling is paired with coached encounters with incidents, refactors, and ethical tradeoffs, not just prompt libraries and hackathons. It means insisting on feedback loops that run long enough to reveal architectural consequences: telemetry that measures not just latency but failure modes, decision audits that trace how generative suggestions changed outcomes, hiring practices that protect time for mentorship instead of only optimizing for short‑term velocity. It means treating philosophical work—questions about responsibility, value, and meaning—not as a luxury, but as part of the design brief. The Pantheon’s builders did not have “principles of technology ethics” in their vocabulary, but they built as if someone would still be standing under that dome long after their names were forgotten. For people shipping AI‑mediated systems now, that is the standard worth aspiring to: not surviving the SaaS‑copalypse news cycle, but leaving behind structures that keep holding when nobody remembers the launch press release.